3/3/24

There are two passages in “Ghosts of My Life.” They caught my attention, but I did not draw any connections until a few days after the fact.

“Savage Messiah rediscovers the city as a site for drift and daydreams, a labyrinth of side streets and spaces resistant to the process of gentrification and ‘development’ set to culminate in the miserable hyper-spectacle of 2012. The struggle here is not only over the (historical) direction of time but over different uses of time. Capital demands that we always look busy, even if there’s no work to do. If neoliberalism’s magical voluntarism is to be believed, there are always opportunities to be chased or created; any time not spent hustling and hassling is time wasted. The whole city is forced into a gigantic simulation of activity, a fantacism of productivism in which nothing much is actually produced, an economy made out of hot air and bland delirium. Savage Messiah is about another kind of delirium: the releasing of the pressure to be yourself, the slow unravelling of biopolitical identity, a depersonalised journey out to the erotic city that exists alongside the business city. The eroticism here is not primarily to do with sexuality, although it sometimes includes it: it is an art of collective enjoyment, in which a world beyond work can – however briefly – be glimpsed and grasped. Fugitive time, lost afternoons, conversations that dilate and drift like smoke, walks that have no particular direction and go on for hours, free parties in old industrial spaces, still reverberating days later. The movement between anonymity and encounter can be very quick in the city. Suddenly, you are off the street and into someone’s life-space. Sometimes, it’s easier to talk to people you don’t know. There are fleeting intimacies before we melt back into the crowd, but the city has its own systems of recall: a block of flats or a street you haven’t focused on for a long time will remind you of people you met only once, years ago. Will you ever see them again?”

(Ghosts of My Life, pp. 211-212, emph. added)

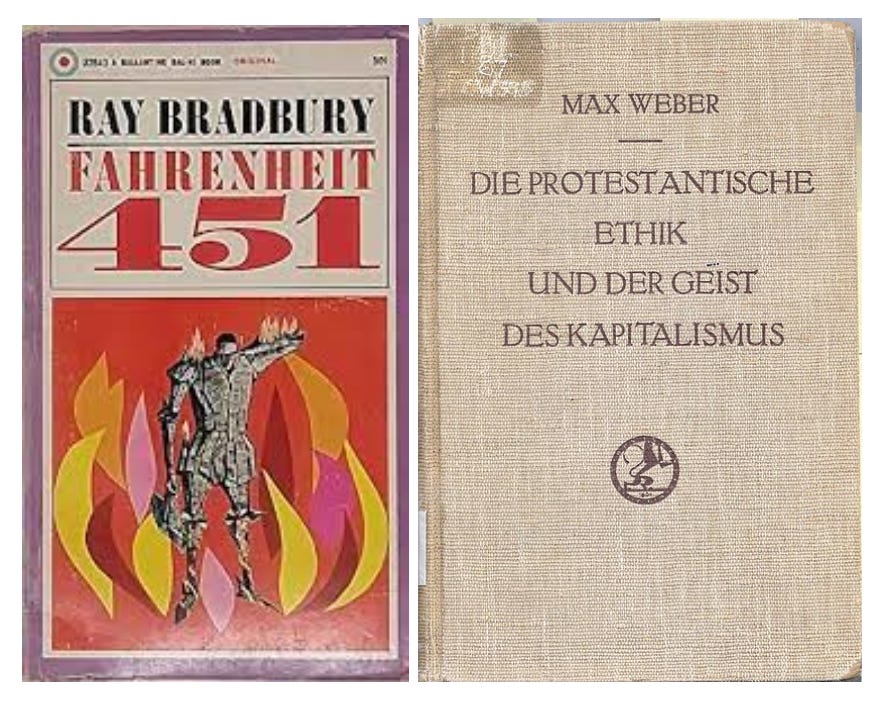

My issue with “fugitive time”, is that the “world beyond work” seems pastoral. This is peak Americana from the streets of Britain. The picture painted is precisely that of Ray Bradbury in “Fahrenheit 451”.

“What was it Clarisse had said one afternoon? ‘No front porches. My uncle says there used to be front porches. And people sat there sometimes at night, talking when they wanted to talk, rocking, and not talking when they didn’t want to talk. Sometimes they just sat there and thought about things, turned things over. My uncle says the architects got rid of the front porches because they didn’t look well. But my uncle says that was merely rationalizing it; the real reason, hidden underneath, might be they didn’t want people sitting like that, doing nothing, rocking, talking; that was the wrong kind of social life. People talked too much. And they had time to think. So they ran off with the porches. And the gardens, too. Not many gardens anymore to sit around in. And look at the furniture. No rocking chairs anymore. They’re too comfortable. Get people up and running around. My uncle says . . . and . . . my uncle . . . and . . . my uncle . . .’ Her voice faded.” (“Fahrenheit 451”, 78).

Even as Bradbury illustrates it, this is Guy Montag’s memory of Clarisse’s memory of her uncle’s memory of a time past. There are four layers of separation from the personal experience of the present, some fourth person’s retelling of some fourth past event. They are drunk on the same nostalgia, the same fantasy as Mark Fisher is here. People used to talk face-to-face. It is Levinas’ ethical dream, really.We have given up the violence of that encounter. The fear of discipline outweighs the fear of connection.

Of course, Bradbury brings it into the “contemplative” register. People need to capital-t “Think”. Bradbury wants a return to truth and reason that is not instrumentalized. On the other hand, Mark Fisher just wants a friend that he could talk to about anything off the cuff. But, both fall into this self-destructive register, blaming some system or authority. Bradbury is echoing Adorno and Horkheimer’s “Dialectic of Enlightenment”, the fight against so-called “instrumental reason” or if gesturing at the irrationality persisting in the positivist project. Or, at least, Bradbury is gesturing toward Max Weber’s acknowledgement of the 20th century’s shift to “economic rationality” and “bureaucratic thinking.” While Adorno is not a fan of Heidegger, he does maintain that this blunt economic control inhibits the development of creative people, Adorno’s own take on the Nietzschean ubermensch. Bradbury, then, is not too far off. What sort of thinking is done on a porch, if not the playful thinking of an “artful” person?

Still, Mark Fisher names biopolitics. He wants you to know that Foucault was correct, and there is a Nietzschean scheme of control keeping people’s docile bodies where they belong. Your consumer identity, and your participation in the hustle culture of resumes, networking, and interviewing—this is your position in the regime of control—this is your surrendering of your sovereignty to your economy.

But, while Mark Fisher does not seem to appeal to “Thought” like Bradbury, we see in a later passage, Fisher does not entirely miss the mark. On a superficial level, it is well known that Bradbury’s spite for the rise of television played a not insignificant role in “Fahrenheit 451”. Mark Fisher himself is not a fan of “new” entertainment, though he appreciates older films.

“Sinatra’s No-One Cares (which could have been subtitled: From Penthouse to Satis House) was like pop’s take on literary modernism, an affect (rather than a concept) album, a series of takes on a particular theme – disconnection from a hyper-connected world – with Frank the ageing sophisticate adrift in the McLuhan wasteland of the late 50s, Elvis already here, the Beatles on the way (who is the ‘no-one’ who doesn’t care if not the teen audience who have found new objects of adoration?), the telephone and the television offering only new ways to be lonely. So This is Goodbye is like a globalised update of No-One Cares, its images of ‘hotel lobbies’, ‘shopping malls we’ll never see again’ and ‘homes for sale’ sketching a world in a state of permanent impermanence (should we say precarity?). The songs are overwhelmingly preoccupied with leavetaking and change, fixated on doing things for the first or the last time. ‘So This is Goodbye’ is not the title track for nothing.” (“Ghosts of My Life”, p. 221)

While it might be a stretch to call Bradbury an enlightenment apologist, it would be even more of a stretch to label Mark Fisher as such. In fact, Mark Fisher’s interest in intellectual culture might shine a light on Bradbury’s own “library” ethos. It is perhaps well known that Bradbury attributes his education to libraries.

Thanks to Visakan Veerasamy for this passage from an interview with Bradbury: “I’m completely library educated. I’ve never been to college. I went down to the library when I was in grade school in Waukegan, and in high school in Los Angeles, and spent long days every summer in the library. I used to steal magazines from a store on Genesee Street, in Waukegan, and read them and then steal them back on the racks again. That way I took the print off with my eyeballs and stayed honest. I didn’t want to be a permanent thief, and I was very careful to wash my hands before I read them. But with the library, it’s like catnip, I suppose: you begin to run in circles because there’s so much to look at and read. And it’s far more fun than going to school, simply because you make up your own list and you don’t have to listen to anyone. When I would see some of the books my kids were forced to bring home and read by some of their teachers, and were graded on — well, what if you don’t like those books?

“I am a librarian. I discovered me in the library. I went to find me in the library. Before I fell in love with libraries, I was just a six-year-old boy. The library fueled all of my curiosities, from dinosaurs to ancient Egypt. When I graduated from high school in 1938, I began going to the library three nights a week. I did this every week for almost ten years and finally, in 1947, around the time I got married, I figured I was done. So I graduated from the library when I was twenty-seven. I discovered that the library is the real school.” (Sam Weller, “Ray Bradbury, The Art of Fiction”. The Paris Review. No. 203. 2010)

In some sense, Bradbury is an anti-intellectual here, or at least, an intellectual outside of the academy, novel as that may be. Again, on the other hand, it is also well-known Mark Fisher gew up working class, received a thorough education in literature in philosophy, then returned to teach philosophy at a further education school and published on his blog. Note that in the UK and Ireland, further education ight follow secondary school but is distinct from higher education of universities. As I understand, it is like community college or vocational school in the US. And, of course, blog publishing is distinct from producing minimal publishable units for academic journals. But Mark FIsher, while perhaps outside the academy, even if not so much as Ray Bradbury, was still an intellectual. Here is a passage where he decries the shift from psychoanalytic thinking to self-help, a theme I continually return to myself.

One aspect of this loss concerns the unconscious itself, and here we might take Nolan’s script quite literally. For those with a psychoanalytic bent, the script’s repeated references to the ‘subconscious’ – as opposed to the unconscious – no doubt grate, but this might have been a Freudian slip of a particularly revealing kind. The terrain that Inception lays out is no longer that of the classical unconscious, that impersonal factory which, Jean-Francois Lyotard says, psychoanalysis described ‘with the help of images of foreign towns or countries such as Rome or Egypt, just like Piranesi’s Prisons or Escher’s Other Worlds’. (Libidinal Economy, Athlone, 1993, 164) Inception’s arcades and hotel corridors are indeed those of a globalised capital, whose reach easily extends into the former depths of what was once the unconscious. There is nothing alien, no other place here, only a ‘subconscious’ recirculating deeply familiar images mined from an ersatz psychoanalysis. So in place of the eerie enigmas of the unconscious, we are instead offered an Oedipal-lite scene played out between Robert Fischer and a projection of his dead father. The off-the-shelf pre-masticated quality of this encounter is entirely lacking in any of the weird idiosyncrasies which give Freud’s case histories their power to haunt. Cod Freudianism has long been metabolised by an advertising-entertainment culture which is now ubiquitous, as psychoanalysis gives way to a psychotherapeutic self-help that is diffused through mass media. It’s possible to read Inception as a staging of this superseding of psychoanalysis, with Cobb’s apparent victory over the Mal projection, his talking himself around to accepting that she is just a fantasmatic substitute for his dead wife, almost a parody of psychotherapy’s blunt pragmatism. (Ghosts of My Life, pp. 242-243).

As Mark Fisher would have it, the new bland culture of the industry has replaced the past intellectual culture of the academy.

Now, I would like a conclusion, but alas. I should be writing delta-epsilon proofs, not writing this. I am glad enough to had found the connections here for nebulously related ideas. There is a pastoral but also anti-intellectual character to Ray Bradbury and Mark Fisher. That is something I can get behind.

Post Script

I feel the above came through for me, but the below is a crippled attempt to say something else. It is a meager collection of online posts. The vague ideas will not come to fruition, but I must include it here to expel it from my body.

3/1/24

I have not written anything lately. At least, it has been a day or two.

I have been thinking a lot about the publishing industry and the decline of academic philosophy.

I have been thinking a lot about how I cannot understand most of what Anna KW says, even though much of it intrigues me.

Thank you, Prof. de Cruz

Helen de Cruz has recently prompted several thoughts for me. First, her substack on “how our focus on prestige in publishing in philosophy prevents us from writing our very best work.” (

)

She also recently published a book, or what she describes as “a beach read”, on how wonder and awe shape out thinking. (https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/199779170-wonderstruck?ac=1&from_search=true&qid=4NFW98Ujee&rank=1)

She also recently tweeted a screenshot of a Daily Nous comment, adding that she is not as into AI as the commenter who wrote: “Philosophy departments are closing one after another, and here we are arguing about the most important thing of all: prestige. Are we asking about whether the journal system is fundamentally flawed? … Are we asking whether absurdly low acceptance rates indicate that the system is merely a lottery? Or an ELO system gamed to produce longer peacock tails? … whether the reviewer crisis or the shift to pay-to-play open access is going to destroy the whole system? … whether book publishing is also fundamentally flawed?... why philosophy books have settled into a deep attractor basin of monotonous style? We could, after all, be using digital technologies to produce some fantastic books, real works of art, but nah, let's just stick to single-column 12 point font, no illustrations please. We could be building an advanced archive with amazing tools for searching and correlating. We could be building cross-linked texts. We could make vast and deep maps and taxonomies. We could be using theorem provers, we could be using Al. We could do so much more, so much more. We have the intelligence, the skill, the imagination. But instead of applying it to our current problems, we're arguing about a status hierarchy. We can do better than this. If we don't, we'll end up like Classics. They were really, really concerned with prestige.”

(https://x.com/Helenreflects/status/1763359170210791611?s=20)

There is a lukewarm argument that: advanced technology, marketing, and mass appeal are not going to save philosophy. But there is also a lukewarm argument that: yes, academic philosophy needs to allow more “soundcloud” philosophers, even if such a description will leave some people cringing. I will gladly favor techne over episteme. But, the rogue, underground movement of technical collaboration is more techne to me than the bleached out over-saturated internet industry or any adjacent sectors. I do not want to be wholly anti-intellectual. That is too easy for me. It would be too easy, and frankly unsatisfying, to write self-cannibalized books with shameless citations of Wikipedia pages like Zizek. I draw no issue with mentioning Wikipedia or with referencing past work, but as a merely anti-intellectual gesture, it is difficult to tolerate.

Thank you Frances K (@pachabelcanon)

I want to return to Frances K’s remark I mentioned a few weeks ago. Philosophy is in some ways about reading primary texts. Reading Différence et répétition or reading L'écriture et la différence both will require an analytical process of picking apart, repeated failure, and return.

This process is very difficult for me. And, I recently saw someone describe literary criticism as “hypochondria” which is apt here. The pleasure I take in reading is tangential, free-associative connections. Re-reading, re-remembering, and re-connecting at immediate, symbolic, and sentimental levels, among others.

Frances K made another remark recently. Why take a computer science class just to gesture toward some social mark of competency? I think again and again about taking an assembly language course at university. It would have been the next computer science course I would have taken should I not have changed to math.

But, there is a third remark from Frances K. He was empathizing with a CS student at some university in the class of 2027, so they will graduate 2 years after me. The CS student said he oscillated between fearing he would flunk out and become homeless and believing he would do PhD research making advances in some technical area.

Anger

The whole reason I started writing this is anger. I wsa distracted by those tangents on Prof. De Cruz and on Frances K.

I missed a question on a quiz yesterday. But, I did everything I could have, in my mind. I set timers, stayed focused while studying, and committed to Cal Newport’s deep work. I do not know if I could have put in more time. I have been trying to take more breaks.

I feel spite towards my secondary education class. And, I have mentioned this before. Now, it is just exhaustion at this point, and I do not want to elaborate. I am not a sociopath. It angers and exhausts me. It is really exhaustion on my face, not sociopathy—I swear.

But, I have been coping lately with this distress and uncertainty, and now this anger—I have been coping with all of this via Nate Soares’ “Replacing Guilt,” which is essentially self-help. I have stopped my obsession with the clusters in the “mental industry” space. Sure, people are peddling superstitions on wall street in the boutiques wedges between finance brokers. Sure, there is some tangential connection between psychoanalysis and self-help.

This is all to say—Mark Fisher’s “Ghosts of My Life” riffs on many issues I have concerned myself with—of course, in his own register. I do not understand half of Mark Fisher’s cultural references, and I only connect with maybe a fourth. I also only have a naive understanding of Jameson, Derrida, and that lot. But he also riffs on the morphing of psychoanalysis into self-help. He writes:

“For those with a psychoanalytic bent, the script’s repeated references to the ‘subconscious’ – as opposed to the unconscious – no doubt grate, but this might have been a Freudian slip of a particularly revealing kind. The terrain that Inception lays out is no longer that of the classical unconscious, that impersonal factory which, Jean-Francois Lyotard says, psychoanalysis described ‘with the help of images of foreign towns or countries such as Rome or Egypt, just like Piranesi’s Prisons or Escher’s Other Worlds’. (Libidinal Economy, Athlone, 1993, 164) Inception’s arcades and hotel corridors are indeed those of a globalised capital, whose reach easily extends into the former depths of what was once the unconscious. There is nothing alien, no other place here, only a ‘subconscious’ recirculating deeply familiar images mined from an ersatz psychoanalysis. So in place of the eerie enigmas of the unconscious, we are instead offered an Oedipal-lite scene played out between Robert Fischer and a projection of his dead father. The off-the-shelf pre-masticated quality of this encounter is entirely lacking in any of the weird idiosyncrasies which give Freud’s case histories their power to haunt. Cod Freudianism has long been metabolised by an advertising-entertainment culture which is now ubiquitous, as psychoanalysis gives way to a psychotherapeutic self-help that is diffused through mass media. It’s possible to read Inception as a staging of this superseding of psychoanalysis, with Cobb’s apparent victory over the Mal projection, his talking himself around to accepting that she is just a fantasmatic substitute for his dead wife, almost a parody of psychotherapy’s blunt pragmatism.”

All I am asking for is a variation of Nate Soares’ “Replacing Guilt” that uses psychoanalysis.

I have been beating myself up. I forget continually that—misery does not correspond to success. Success is about working smart not working hard. Sure, you must put in effort, but results correspond to strategy just as much if not more than effort. Sacrifice is not even part of this game. Soares explains that there is no reward for burning yourself out—that working 60 hour weeks is not sustainable. You have to recognize that your time, energy, and focus are finite. While you can always strive to push yourself more, don’t act like you can become superhuman. This acknowledgement of immediate finitude (which I do not want to conflate with the finitude of the whole universe, et cetera) addresses all of my overvalued ideas: Aurelius, Nietzsche, Frankl, Maslow, Singer, and all that. I need to allocate my personal resources without reducing myself to my personal resources—a slogan I repeat to myself lately.

—

Now I have deleted a bad tweet today and two bad replies. How can one turn the neurotic defense of intellectualization into the mature defense of sublimation?